Burials of Teganshire Post 5 of 30

So much has been said about making good villains for the D&D campaign that rehashing Villanous Design Philosophy is both superfluous and probably dull. Let’s just give you some! Here are six villans with motivations and that personalized touch to keep your players interested in the campaign world. We follow that up tomorrow with some villain integration tips—the mechanics of inserting the PCs nemesis into the game world.

Shall we begin?

The PCs Personal D&D Villains at Home

The Villainous Villains await!

1: CheryLynn, Vampire at Large

Long ago, a charismatic but lonely vampire stayed at the local inn, and, enamored with one of the peasant girls, engaged in a torrid affair that resulted in CheryLnn becoming a vampire herself. Ashamed at turning another woman into a damned thing, the master vampire fled, chased by an enraged CheryLnn. She eventually caught up to him and slew him. CheryLnn, wandering here and there, decided after a long while to research her affliction to cure it.

Lady CheryLnn is now an educated, but wicked, vampire with extensive wizard capabilities. She is convinced the path to a cure is running experiments on people related to her. After all these years, that is a considerable number of the local area’s inhabitants. All she wants is to be the girl she was so long ago and will let nothing stand in her way.

2. Ranger Gifford the Vigilante’s Sword

Witnessing a crime from a minor noble, the ranger Gifford took it upon himself to avenge the innocent outside of the King’s Law. And he got away with it. He’s been an unsung hero since, righting wrongs and punishing the guilty behind the scenes.

Unfortunately, Gifford’s actions are the direct manipulation of his corrupted, mighty longsword that whispers to him while he is sleeping, invading his dreams and replacing his original personality with one of its own choosing. Now it is turning Gifford into a captivating cult leader, to “gather the righteous for the True Inquisition.”

3. Yonson the Werewolf

Yonson is an anomaly of sorts—when he turns into a werewolf, he has a modicum of control over his great rage and viciousness. He plots to quietly take over the region, convinced that he is chosen to lead people into a better state of existence. Yonson is also motived by a series of odd images he received. After dragging a deer into a cave behind a waterfall to munch in private, he touched an old magical tablet and received a vision. Something thoroughly malevolent and destructive will be coming to the area, an ancient prophecy coming to fruition.

Yonson, in his mind, is doing all the right things, at any cost. If the PCs defeat him, they will have to deal with his nemesis alone, without the werewolf army.

4. The Dragon Duo

Moving into the local forest is a young green dragon, bent on turning the whole into a “proper wood where only the strong can tread.” Cagey, avoiding direct conflict, and devious, the green causes no end of trouble for the region.

When the PCs figure it out and decide to deal with the dragon, they are approached by a woman with a silver streak in her hair. She tells them the green is the last offspring of a famous, ancient green, and she was tasked to make sure nobody kills him before he’s able to learn the ways of men and avoid the King’s Dragon Hunters and preserve his great lineage. She claims to be a silver dragon named Missy and wants the PCs to capture the green and move him somewhere else without implicating her involvement.

If the PCs thought the green was bad, Missy is completely bad, a mighty dragon lich wanting the green for her own fell purposes. She is telling a half-truth—the green is the last of his line, but the forest contains a powerful warding stone against the undead. Missy wants to dupe the PCs to be her unwitting servants, turn the green into a lich, and destroy the warding stone.

5. Lord Marthous and the Lady

Lord Marthous and his wife are on the lam, hiding from the King’s Men. Lord Marthous recently found out he was the bastard son of the king and confronted the nobleman he thought was his father and also his mother for her discretion. The confrontation escalated out of control, and while fighting his step-father, his mother interjected herself in front of a mighty sword blow and died. Marthous in a rage then slew his step-father.

Hunted, despised for patricide, Lord Mathous and his wife fled but ran into a trio of paladins hunting them, the three not realizing that the Lady was a sorcerer with powers of her own. The duo slew the young knights.

Now Marthous is done running. He plans to clear his name by usurping the throne. He will replace the King, the man in his mind, the cause of all his troubles. He makes an impassioned plea for the PCs to help him. If the PCs join him, when he is successful in his plot, he will reward them with betrayal! He will blame them for the atrocities committed to ascend the throne (guilty or not) in order to appease the nobles still on the fence.

If the PCs refuse him upfront, he becomes a bitter enemy, and the King solicits their help in the dispute.

Either way, the PCs at some point will probably ask—are we the baddies?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hn1VxaMEjRU

6. Fey Gone Wild

Teamai, the elf druid, has in her possession a fey stone, a magical device that lets her summon fey to do her bidding. She has decided that she wants to take over her people’s ancestral lands, the place where the PCs are from. Young, idealistic, and charismatic, she wages a passive-aggressive war against the region, to have the populous rebel against the “wicked tyranny of the nobles” and replace them with her “rightful, benevolent rule.” It escalates, and people die.

PCs can convenience Teamai to stop her reign of terror or defeat her, but the fey stone has other ideas, turning to dust and seeping into her brain to directly control her (either alive or dead). Complicating matters a powerful elf matriarch shows up and pleads with the PCs to save her daughter, the rest of her children perished in war and Teamai is all she has left. And the nobles have plans of their own to protect themselves by doing away with the elves, who will respond in kind. Now, in addition to battling the fey stone zombie that is Teamai, genocide is staring at them in the mirror.

Want some more D&D or Pathfinder 1E Villains?

Back Burials of Teganshire on Indiegogo and get on some tragic villainy!

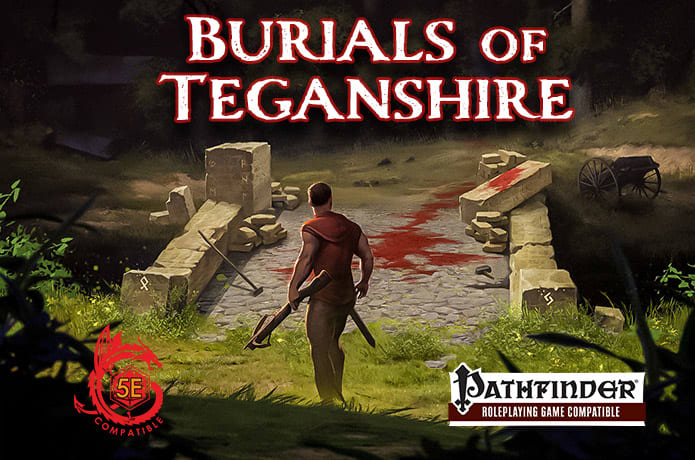

I bet Crossbow Man thinks the monster at the bridge is the real enemy.